The Origins of Islam: A Historical Overview

Islam’s emergence in the 7th century, rooted in Prophet Muhammad’s revelations, dramatically altered the Arabian Peninsula’s religious and political landscape, initiating a profound history.

Pre-Islamic Arabia: Religious Landscape

Prior to the advent of Islam in the 7th century, the Arabian Peninsula presented a complex and diverse religious tapestry, largely characterized by polytheism. The dominant belief system revolved around the worship of numerous deities, often associated with natural forces and celestial bodies. A rather primitive polydemonism, as described by sources, was prevalent, with tribes venerating local gods and goddesses housed in sacred spaces like the Kaaba in Mecca.

Worship extended beyond deities to include the reverence of stones, stars, caves, and trees – demonstrating a deep connection to the natural world. This animistic element was interwoven with the polytheistic framework. While Judaism and Christianity had established smaller communities within Arabia, their influence remained limited. The prevailing spiritual climate lacked a centralized religious authority or a unified theological doctrine, fostering a fragmented religious landscape ripe for a transformative message. This context is crucial for understanding the impact of the Prophet Muhammad’s revelations.

The Prophet Muhammad: Early Life and Revelations

Prophet Muhammad, born in Mecca around 570 CE, emerged during a period of significant social and spiritual upheaval in Arabia. Initially, he was known for his honesty and trustworthiness, earning the title “al-Amin.” Around A.D. 610, Muhammad began receiving what he believed to be divine visions, experiences that profoundly shaped his life and ultimately led to the founding of Islam.

These visions culminated in the first revelation, delivered by the Archangel Gabriel (Jibrail in Arabic), instructing him to “recite in the name of your lord.” These early revelations focused on the existence of a single, all-powerful God, directly challenging the polytheistic beliefs prevalent at the time. Muhammad’s initial followers faced persecution, prompting a period of hardship and ultimately, the pivotal migration to Medina.

The First Revelation: Encounter with Gabriel

The initial revelation, a cornerstone of Islamic belief, occurred around 610 CE while Prophet Muhammad was meditating in a cave on Mount Hira, near Mecca. The Archangel Gabriel (Jibrail) appeared to Muhammad, commanding him to “recite in the name of your lord.” This encounter was a deeply transformative experience, marking the beginning of Muhammad’s prophetic mission.

Initially overwhelmed, Muhammad struggled to comprehend the divine message. Gabriel’s repeated instructions and the subsequent revelations gradually clarified the core tenets of Islam: the absolute oneness of God (Tawhid) and the rejection of idolatry. This first revelation directly contradicted the prevailing polytheistic practices of pre-Islamic Arabia, where worship of stones, stars, and various deities was commonplace. It laid the foundation for the Quran, Islam’s holy book, and the faith’s central message.

The Quran: Compilation and Significance

The Quran, considered by Muslims to be the literal word of God (Allah), wasn’t initially compiled as a single book. Revelations received by Prophet Muhammad over approximately 23 years were memorized and recorded on various materials – palm leaves, stones, and animal hides. Following Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, the need for a standardized text became paramount.

During the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan (644-656 CE), a committee was established to collect and compile the scattered verses into a single, authoritative volume. This standardized version, known as the Uthmanic codex, became the foundation for all subsequent Quranic manuscripts. The Quran’s significance lies in its role as the ultimate guide for Muslims, encompassing religious, ethical, and legal principles. It serves as a source of truth and a comprehensive framework for Islamic thought and practice.

The Rise of Islam in the 7th Century

Islam’s rapid expansion throughout the 7th century, beginning with the Hijra, established a new political and religious order across Arabia and beyond.

Early Followers and the Formation of the Ummah

The initial reception of Prophet Muhammad’s message was mixed, facing opposition from established tribal leaders in Mecca. However, a core group of early followers, including close family and friends, embraced Islam and formed the foundational community, known as the Ummah. These individuals played a crucial role in preserving and disseminating the new faith during times of persecution.

Key figures like Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman were among the first to accept Islam, providing unwavering support to the Prophet. Their loyalty and dedication were instrumental in establishing the early Muslim community. The Ummah wasn’t merely a religious congregation; it was a social and political entity built on principles of mutual support, justice, and shared belief. This sense of collective identity proved vital for the survival and eventual triumph of Islam, fostering a strong bond among believers and laying the groundwork for the expanding Islamic empire.

Migration to Medina (Hijra): A Turning Point

Facing escalating persecution in Mecca, Prophet Muhammad and his followers undertook a pivotal journey to Medina in 622 CE, known as the Hijra. This migration marked a turning point in the history of Islam, signifying a shift from a vulnerable, marginalized community to one with the potential for political and military strength.

In Medina, Muhammad was invited to serve as a leader and arbitrator, establishing a new social contract. The Hijra wasn’t simply an escape; it was a strategic relocation that allowed Islam to flourish. It provided a safe haven for believers and enabled the Prophet to consolidate his authority and build a more robust community. This event is so significant that the Islamic calendar begins with the year of the Hijra, highlighting its foundational importance in shaping the trajectory of Islamic civilization and its subsequent expansion.

The Constitution of Medina: Establishing a Community

Upon arriving in Medina, Prophet Muhammad skillfully forged a unique social and political framework – the Constitution of Medina. This document, drafted in 622 CE, represented a groundbreaking attempt to establish a pluralistic community encompassing Muslims, Jews, and other tribes inhabiting the city. It outlined principles of mutual cooperation, justice, and defense against external threats, effectively creating a unified Ummah.

The Constitution guaranteed religious freedom for all, while simultaneously establishing a system of collective security and dispute resolution. It addressed issues of warfare, property rights, and legal procedures, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of governance. This landmark agreement, a cornerstone in early Islamic history, showcased Muhammad’s leadership and his commitment to building a cohesive and equitable society, laying the groundwork for future Islamic states.

Battles and Conflicts: Establishing Islamic Authority

The early years of Islam were marked by a series of battles and conflicts, primarily with the Quraysh of Mecca, who initially opposed Muhammad’s teachings. Key engagements like Badr (624 CE) and Uhud (625 CE) were pivotal in establishing the growing Muslim community’s strength and resilience. While facing setbacks, these conflicts demonstrated the unwavering faith and determination of the early Muslims.

The Battle of the Trench (627 CE) proved decisive, successfully defending Medina against a larger Quraysh force. Ultimately, the peaceful conquest of Mecca in 630 CE signified a turning point, solidifying Islamic authority throughout Arabia. These military encounters, documented in early Islamic history, weren’t solely about conquest; they were crucial in consolidating power and spreading the message of Islam, shaping the nascent Ummah’s identity and future trajectory.

The Early Caliphates (632-661 CE)

Following Muhammad’s death, the Rashidun Caliphate emerged, led by Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali, initiating a period of rapid expansion and consolidation.

Abu Bakr: The First Caliph and Consolidation of Power

Abu Bakr (632-634 CE), a close companion and father-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, became the first Caliph after Muhammad’s passing. His immediate challenge was stabilizing the nascent Islamic community facing internal dissent and external threats. The “Ridda Wars” (Wars of Apostasy) erupted as several Arab tribes withdrew their allegiance, refusing to continue paying zakat (alms) and some even claiming prophethood.

Abu Bakr swiftly and decisively responded, dispatching armies led by prominent commanders like Khalid ibn al-Walid to quell the rebellions. These campaigns, though initially controversial, were ultimately successful in re-establishing Islamic authority across Arabia. He authorized the compilation of the Quran, a crucial step in preserving the divine revelation.

Furthermore, Abu Bakr initiated early administrative structures, laying the groundwork for future Islamic governance. His short but impactful caliphate was pivotal in consolidating the power of Islam and setting the stage for subsequent expansion, ensuring the survival and growth of the newly formed Islamic state.

Umar ibn al-Khattab: Expansion and Administration

Umar ibn al-Khattab (634-644 CE), the second Caliph, oversaw a period of remarkable expansion and administrative development. Building upon Abu Bakr’s foundations, Umar directed military campaigns that led to the conquest of vast territories, including Syria, Egypt, and Persia – previously major centers of the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. These victories dramatically reshaped the geopolitical landscape.

Recognizing the need for effective governance, Umar implemented a sophisticated administrative system. He established a centralized treasury (Bayt al-Mal), standardized weights and measures, and created a provincial administration with appointed governors and officials. A rudimentary form of public welfare was also introduced, providing stipends to the needy.

Umar’s reign also saw the development of early Islamic legal practices and the construction of infrastructure like canals and roads. His justice and piety earned him the title “al-Farooq” (the discerning one), solidifying his legacy as a pivotal figure in early Islamic history and a masterful administrator.

Uthman ibn Affan: Quranic Canonization and Internal Strife

Uthman ibn Affan (644-656 CE), the third Caliph, is primarily remembered for his crucial role in standardizing the Quran. Recognizing variations in recitation across the expanding Islamic empire, Uthman commissioned a committee to compile an official, authoritative version – the Mushaf – based on the existing written fragments and oral traditions. This canonization ensured the preservation of the divine revelation.

However, Uthman’s reign was also marked by growing internal strife. Accusations of nepotism, favoring his clan (the Umayyads) in appointments to key positions, fueled discontent. Critics alleged unfair distribution of wealth and a shift towards a more centralized, autocratic style of rule; These grievances culminated in open rebellion and ultimately, Uthman’s assassination in 656 CE, plunging the early Muslim community into a period of civil war – the First Fitna.

Ali ibn Abi Talib: Challenges and the First Fitna

Ali ibn Abi Talib (656-661 CE), the fourth Caliph and cousin of Prophet Muhammad, ascended to leadership amidst immense turmoil following Uthman’s assassination. His caliphate was immediately challenged by internal dissent and the outbreak of the First Fitna, a devastating civil war. Key figures like Talha and Zubayr, along with Aisha, questioned Ali’s legitimacy and demanded retribution for Uthman’s death.

This led to the Battle of the Camel (656 CE), a pivotal clash within the Muslim community. Simultaneously, Muawiyah, the governor of Syria and a relative of Uthman, refused to pledge allegiance to Ali, accusing him of complicity in Uthman’s murder. This marked the beginning of a prolonged power struggle. Ali’s reign was characterized by constant warfare and political maneuvering, ultimately ending with his assassination in 661 CE, further deepening the divisions within the nascent Islamic world.

The Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE)

Umayyad rule, beginning in 661 CE, witnessed vast territorial expansion across North Africa and into Spain, alongside centralized administrative reforms and growing internal strife.

Expansion of the Islamic Empire: North Africa and Spain

Following the death of Prophet Muhammad, the Islamic empire rapidly expanded beyond the Arabian Peninsula, notably into North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). Initial forays into North Africa began in the 7th century, encountering resistance from the Byzantine Empire and local Berber tribes. However, through a combination of military conquest and treaties, Islamic control gradually extended westward along the North African coast.

A pivotal moment arrived in 711 CE with the Umayyad conquest of Visigothic Spain, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad; This invasion swiftly dismantled the Visigothic kingdom, opening the door for Islamic rule over much of Iberia. The newly conquered territory, known as Al-Andalus, flourished as a center of learning and culture for centuries. This expansion wasn’t merely military; it involved cultural exchange and the establishment of Islamic institutions, profoundly shaping the region’s history and leaving a lasting legacy.

Centralization of Power and Administrative Reforms

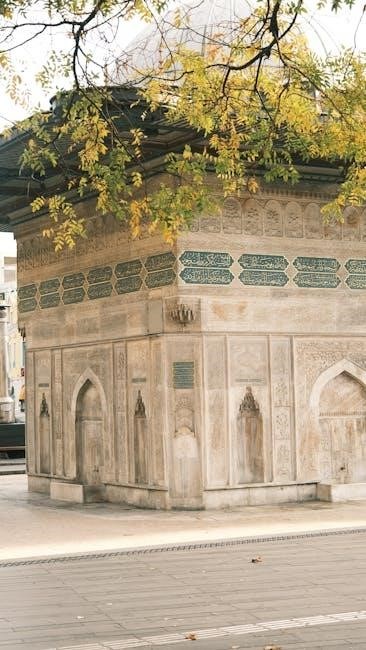

The Umayyad Caliphate, seeking to govern its vast and rapidly expanding empire, implemented significant centralization of power and administrative reforms. Departing from earlier, more decentralized approaches, the Umayyads established a more structured and hierarchical system. Damascus became the imperial capital, serving as the central hub for governance and decision-making.

Key reforms included the standardization of coinage, the establishment of a postal service (barid) for efficient communication, and the development of Arabic as the official language of administration. Provincial governors, often members of the Umayyad family, were appointed to oversee regional affairs, but were increasingly accountable to the central authority. These changes aimed to enhance revenue collection, maintain order, and consolidate the Caliphate’s control over its diverse territories, fostering a more unified and efficient empire.

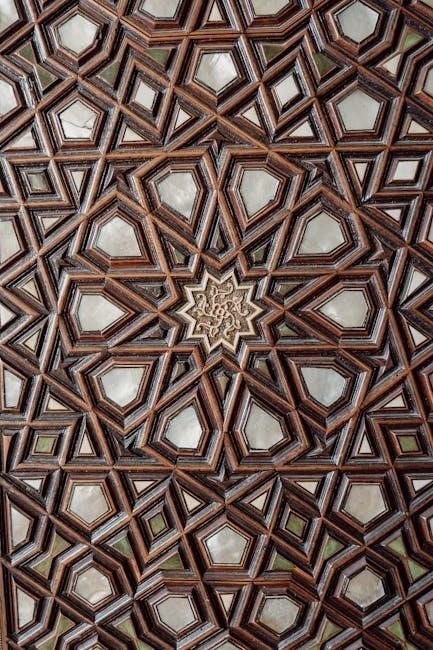

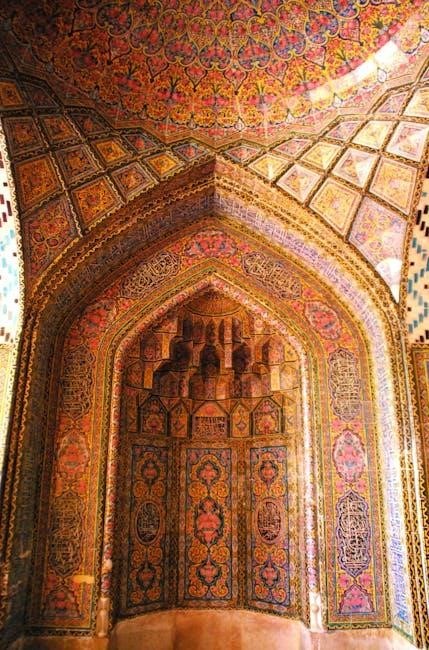

Cultural Developments under the Umayyads

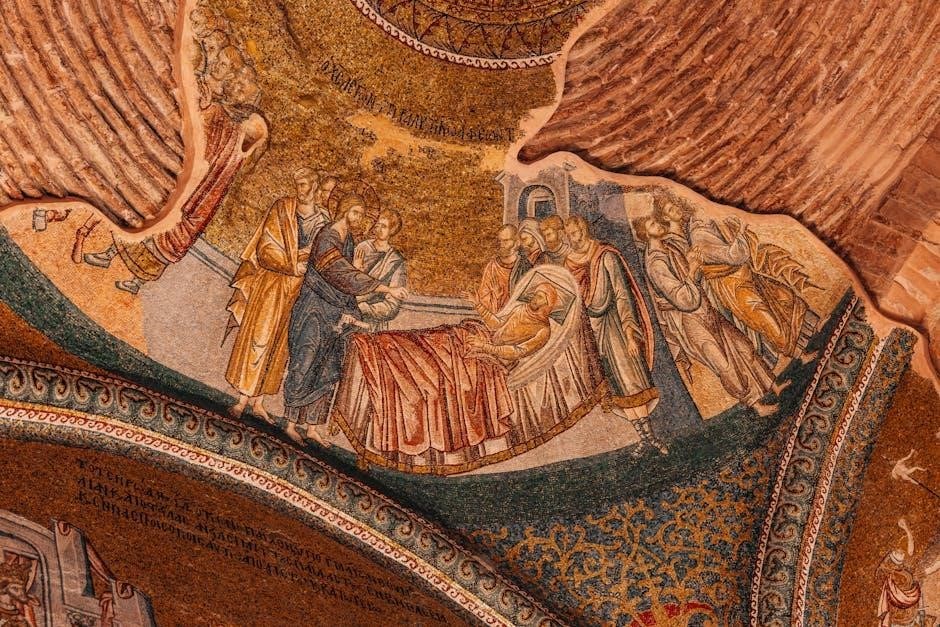

Despite facing political challenges, the Umayyad period witnessed notable cultural developments, blending Arab traditions with those of conquered regions. Architectural innovations flourished, exemplified by the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus, showcasing intricate mosaics and grand designs. Arabic poetry reached new heights, becoming a refined art form at the court.

The Umayyads also facilitated the transmission of knowledge, benefiting from the intellectual heritage of Greece, Persia, and India. While not a period of extensive translation, foundations were laid for the later Abbasid “Golden Age.” Scholarship in areas like medicine and mathematics began to emerge. Though often focused on practical applications for administration and warfare, these early developments signaled a growing intellectual curiosity within the expanding Islamic world, shaping its future cultural landscape.

The Second Fitna and the Decline of the Umayyads

The Second Fitna, a period of widespread rebellion and civil war, significantly weakened the Umayyad Caliphate. Rooted in disputes over succession and fueled by grievances from marginalized groups – particularly non-Arab Muslims and Shi’a – the conflict fractured the empire. The rise of various factions, including the Kharijites and Alids, challenged Umayyad authority across vast territories.

Internal strife, coupled with increasing administrative burdens and perceived corruption, eroded public support. While the Umayyads initially suppressed major uprisings, the constant warfare drained resources and exposed vulnerabilities. The growing discontent ultimately culminated in the Abbasid Revolution, led by descendants of the Prophet’s uncle, Abbas. This revolution, capitalizing on widespread dissatisfaction, successfully overthrew the Umayyads in 750 CE, marking a pivotal shift in Islamic history and ushering in a new era.

The Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE)

Abbasid rule, beginning in 750 CE, signified a dramatic power shift and inaugurated a golden age of intellectual and cultural flourishing within the Islamic world.

The Abbasid Revolution and Shift in Power

The Abbasid Revolution, a pivotal moment in Islamic history, dramatically overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 CE. This wasn’t merely a change in leadership; it represented a fundamental shift in the very foundations of Islamic governance and societal structure. The Umayyads, often criticized for their perceived favoritism towards Arab Muslims and their increasingly secular administration, faced growing discontent from various groups, including non-Arab Muslims (mawali), Shi’a Muslims, and those who felt marginalized by Umayyad policies.

The Abbasids, descendants of the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, skillfully exploited this widespread dissatisfaction. They presented themselves as champions of religious piety and social justice, promising a more inclusive and equitable rule. Their revolutionary movement, carefully orchestrated and strategically supported, culminated in a decisive victory at the Battle of the Zab in 750 CE, effectively ending Umayyad dominance.

The Abbasids relocated the capital from Damascus to Baghdad, strategically positioning it as a new center of power and learning. This relocation symbolized a deliberate move away from the Umayyad’s Arab-centric policies and towards a more cosmopolitan and inclusive empire.

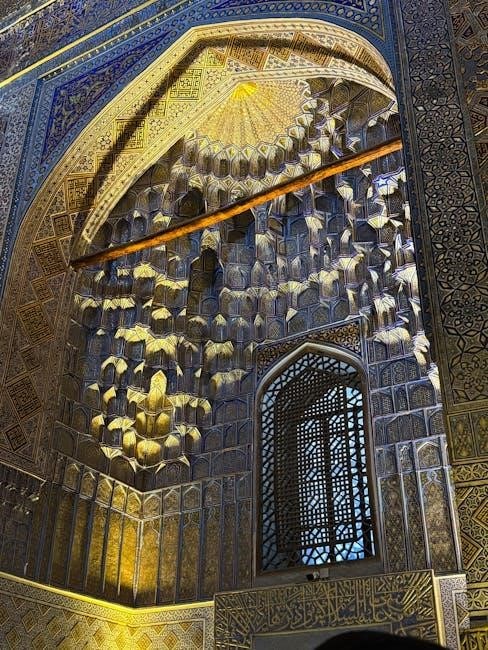

The Golden Age of Islam: Intellectual and Scientific Advancements

The Abbasid Caliphate ushered in a remarkable period known as the Golden Age of Islam, roughly spanning the 8th to the 13th centuries. This era witnessed an unprecedented flourishing of intellectual and scientific pursuits, building upon Greek, Persian, and Indian knowledge, and making significant original contributions. Baghdad, as a central hub, attracted scholars from diverse backgrounds, fostering a vibrant exchange of ideas.

Advancements were made in numerous fields, including mathematics – with the development of algebra by Al-Khwarizmi – astronomy, medicine, optics, and chemistry. Islamic scholars translated and preserved classical texts, preventing their loss during Europe’s Dark Ages. Hospitals, like those established in Baghdad, were pioneering medical institutions, emphasizing hygiene and patient care.

This period also saw significant literary and philosophical achievements, with renowned figures like Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Al-Farabi making lasting impacts. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad served as a major translation and research center, solidifying Islam’s role as a beacon of learning.

Baghdad as a Center of Learning and Culture

During the Abbasid Caliphate, Baghdad rapidly transformed into a global epicenter of intellectual and cultural life, eclipsing many contemporary cities. Strategically located on ancient trade routes, it facilitated the exchange of knowledge and goods from across the known world. The city’s cosmopolitan atmosphere attracted scholars, scientists, and artists from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds.

The establishment of the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) was pivotal, functioning as a library, translation institute, and research center. Scholars meticulously translated Greek, Persian, and Indian texts into Arabic, preserving invaluable knowledge. Baghdad’s libraries amassed vast collections, becoming magnets for learning.

Beyond scholarship, Baghdad flourished in the arts, literature, and architecture. Its bustling markets, magnificent mosques, and opulent palaces showcased the empire’s wealth and sophistication. The city’s vibrant cultural scene fostered innovation and creativity, leaving an enduring legacy on Islamic civilization.

Fragmentation and the Rise of Independent Dynasties

By the 10th century, the vast Abbasid Caliphate began a gradual decline, marked by diminishing central authority and increasing regional autonomy. Provincial governors and military commanders asserted their independence, establishing hereditary dynasties that challenged the Caliph’s control. This fragmentation wasn’t a sudden collapse, but a protracted process spanning several centuries.

Powerful dynasties like the Buyids in Persia and the Fatimids in Egypt emerged, often recognizing the Abbasid Caliph symbolically while exercising de facto rule in their respective territories. These independent entities fostered distinct cultural and political identities, contributing to the diversification of the Islamic world.

Despite the political fragmentation, trade and intellectual exchange continued, albeit along altered routes. The rise of independent dynasties ultimately led to a more decentralized Islamic landscape, characterized by regional power centers and diverse interpretations of Islamic faith and practice.

Islamic Theology and Practices

Islamic faith centers on Tawhid (oneness of God), guided by the Quran and Sunnah, manifesting in the Five Pillars – core beliefs and rituals for Muslims.

The Five Pillars of Islam: Core Beliefs and Rituals

The Five Pillars represent the foundational acts of worship in Islam, embodying a Muslim’s commitment to God and the community. Shahada, the declaration of faith, affirms “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is his messenger,” establishing monotheism. Salat, or prayer, is performed five times daily, fostering a direct connection with the Divine.

Zakat, obligatory charity, promotes social justice and wealth redistribution, purifying one’s possessions. Sawm, fasting during Ramadan, cultivates empathy and spiritual discipline. Finally, Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, if physically and financially able, unites Muslims globally in a shared act of devotion.

These pillars aren’t merely rituals; they are expressions of submission, gratitude, and a striving for moral excellence, deeply interwoven with the historical development and theological underpinnings of Islam.

Sunnah: The Practices and Teachings of the Prophet Muhammad

The Sunnah encompasses the words, actions, and approvals of Prophet Muhammad, serving as a vital source of guidance for Muslims alongside the Quran. It’s meticulously documented in Hadith collections, narrations detailing his life and teachings, offering practical application of Islamic principles. Understanding the Sunnah is crucial for interpreting the Quran and navigating daily life according to Islamic ethics.

The Sunnah covers a vast spectrum – from ritual practices like prayer and fasting to social conduct, ethical considerations, and legal rulings; It provides a model for moral character, emphasizing compassion, honesty, and justice. Different schools of thought exist regarding Hadith authentication and interpretation, leading to variations in Sunnah application.

Historically, preserving and transmitting the Sunnah was paramount, shaping Islamic jurisprudence and fostering a continuous connection to the Prophet’s legacy.

Islamic Beliefs: Tawhid, Prophethood, and the Day of Judgement

Central to Islamic faith are core beliefs defining humanity’s relationship with God. Tawhid, the absolute oneness of God, rejects any form of polytheism or associating partners with Him, forming the foundation of the religion. Prophethood affirms God’s communication through prophets, with Muhammad considered the final messenger, building upon the legacies of Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.

Belief in the Day of Judgement—a future reckoning where individuals are held accountable for their actions—instills moral responsibility and emphasizes the importance of righteous conduct. This belief encompasses divine justice, reward for the faithful, and consequences for wrongdoing.

These tenets, deeply rooted in the Quran and Sunnah, shape Islamic worldview and ethical framework, influencing personal and communal life throughout history.

The Development of Islamic Law (Sharia)

Sharia, often translated as “the path,” represents the comprehensive legal system of Islam, derived from the Quran and the Sunnah (Prophet Muhammad’s teachings and practices). Its development wasn’t instantaneous but evolved over centuries through scholarly interpretation and consensus (ijma) and analogical reasoning (qiyas).

Early legal schools emerged in cities like Medina, Kufa, and Baghdad, each contributing to the systematization of legal rulings covering diverse aspects of life – worship, family, commerce, and criminal justice. These schools, including Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali, represent differing methodologies.

Throughout history, Sharia has served as a guiding framework for Muslim societies, influencing governance, ethics, and social norms, though its implementation has varied across time and place.